If I recall correctly, my last June post was in part a celebration and analysis of musicals, in particular my endless fascination with the changes in the form in the 20th century - those that Stephen Sondheim mentor Oscar Hammerstein (South Pacific, Oklahoma, Carousel) wrought by bringing an explicitly progressive, liberal, and yes, at times sentimental, book-and-story conscious sensibility to the form.

Yet, as followers of our podcast must surely know by now, that is but one example of the many variations that an art form can take. And I do aim to have representatives of differing styles on my show.

My interests tend towards the encyclopedic; I believe I can encompass both breadth and depth in my continuous research.

And I am literally learning new things every day.

A long time ago, in the early 1990s to be exact, a very close friend at the time remarked about my breadth of diverse tastes.

I think he was genuinely puzzled at the fact that I both loved the movies I discussed in last month post, Jacque Rivette, Andrei Tarkovsky and so on but was also positive in my estimation of say, Threes Company. Interestingly at the time I did not have a lot of quick responses since I had not even discovered pluralism as a concept yet and I was only acquainted with some very difficult literature on aesthetics and theory that I had happened to have been taught at that time - mainly in the late 1980s.

What I would say today is that art is also plural, is many things, not a single thing. And one of those things is this "snapshot" character. Any snapshot take a lot of work, sometimes "blood, sweat, and tears" just for there to be this one snapshot. I would say people forget that too often and my podcast might hopefully be a reminder of that. And I also try to keep in mind the need for different values; I always prefer some art to others and it is never all the same to me, but I have an aesthetic curiosity that is as important as most evaluations.

Then there is the question of documentation of historical changes in real time. This is also something with our podcast is connected. I often feel as if the world around me and the ground under the feet is shifting so quickly and so incessantly that perhaps this might be one reason why the archival and preservationist parts of my character have come to the fore these past few years.

It is not just this 1970s book, though that is a great part of it: it is some interest in expressing to the world, one means of which is this podcast, the possibility and at times even the actuality that art mediums, though appearing disparate and separated by vast expanse of times and eras and considerations both commercial and civic, have some kind of connection by virtue of human creation, but creation outside of the flow of so-called real life.

This is what I would the representational character of what we call art.

To "represent" is to create a halt or "time out" from ordinary or real life so as to reflect on that life. What we call art is a concrete result of this reflection.

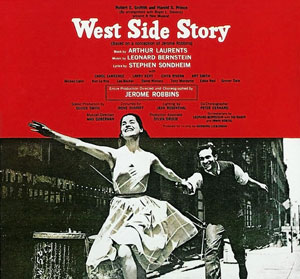

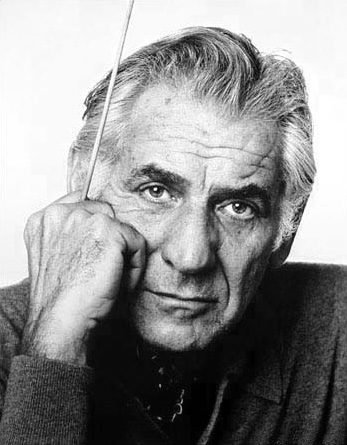

Looked at in this way I might have as much interest in the Steven Spielberg/Tony Kushner version of Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim's West Side Story from this past year as I do in the most obscure and forgotten t.v. movie from forty years ago.

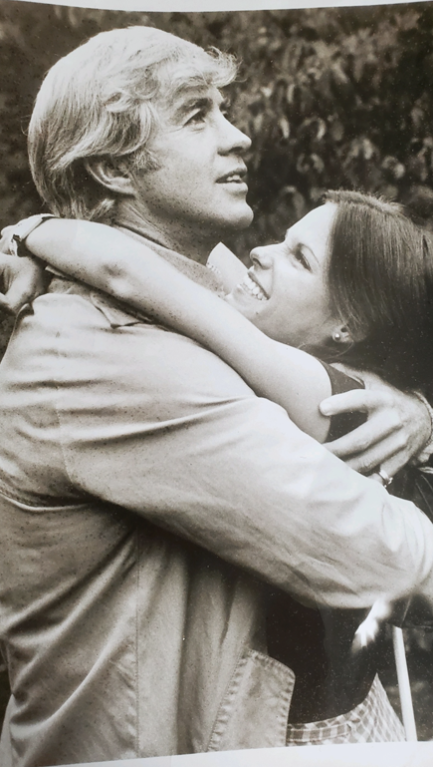

I am thinking of the latter because, in organizing my archival material this season, I came across a publicity still that I must have purchased from one of my favorite bookstores in the entire United States: Larry Edmunds Bookshop in the heart of Hollywood. Now this was one one my precious few trips to that city, I believe in 2015, before I had become more interested in the t.v. movies of that era.

Though I did acquire this photo and saved it on my move. The film appears to be one of many forgotten or lost-to-the-ethers productions of that era.

I happen to be an enormous fan of Kay Lenz, in particular her work in the Clint Eastwood and Jo Heims picture Breezy. (Jo Heims wrote two of my favorites from this period also involving Eastwood, the other being Play Misty For Me). And many might remember Clu Gallagher from The Virgninian.

All of this brings to mind the Tarantino picture that I saw twice in theaters, Once Upon A Time In Hollywood. (I am firmly of the opposite camp than Pauline Kael on this issue. She was proud of getting or appreciating a film by only seeing it once, and this being a key to its superior virtue. I think a really superior picture demands to be seen more than once to fully even get it.)

There is something of the sensibility and milieu of this Heart In Hiding movie that evokes the spirit of Tarantino's picture.

Whatever else we could say about that picture, it is really a film about this love for all the actors and stunt people that worked in both television and movies. There is an elegiac mode of tribute in that picture that connects in some way to our podcast. It is a specific way of regarding people in the arts, including performers and actors. Indeed, I think what the picture is really "about" is whether as a culture we value the processor artistic creation itself, or like the Manson Family, condemn it. (One of the Manson girls has an important monologue in the picture attacking Hollywood for its products and star and I read her as Tarantino's main opponent, notwithstanding murder) Chuck Klosterman expressed this ethic well in his book The Nineties: "Tarantino wanted Travolta in Pulp Fiction for the same reason he'd liked Travolta in Urban Cowboy and Saturday Night Fever and Welcome Back Kotter. The culture may have shifted, but -within the miles of the video store - all those performances remained unchanged."

Now maybe one day I will come upon a copy of Hear In Hiding. Maybe I will have to take a trip to the Museum of Television and put on the headphones. I really don't know. But I do have this one publicity still. It certainly is a snapshot of sorts and my saving of it provides a continuity between the past and present.

The whole question of eras and the popularity of this or that commercial production is in itself a rather big topic. To name but one example, the ratings for the finale of The Big Bang Theory, a show I have not as of yet watched, was about 18 million viewers. that might seem like a large number but not when compared to that long era of consensus/analog culture, especially the 1970s and 80s. Since the choice was so comparatively small as to what art to consume, there really was something like a general public and t.v. movies much like my example were something of a national event.

For example the lowbrow Horror At 37,000 Feet from 1974 with William Shatner was seen by 26 million people. The decidedly higher brow The Day After, from 1983, was seen by one hundred million people! This goes to show of course that the prospect of the end of human and other life on earth from nuclear war is more compelling than the prospect of the end of life of the passengers aboard a single airplane from a demon in the baggage department.

But these amusing as well as important sociological examples point to the inevitable and incessant fact that as an aesthete I will also have to incorporate the fact that people receive culture in ways other than aesthetic ones. That they will see John Travolta as in ways other than the way I or, so it appears, Quentin Tarantino sees him.

Though on this podcast I do "privilege" the aesthetic, the growth of niche culture and various subcultures -the dissolution of consensus - will continue to play a role in artistic production as well as reception.

This post is my point of view but hopefully I have expressed why I happen to hold that point of view and why a t.v. movie made for the afternoon in another era might hold some value.

Comments